With the 2020s well underway, we’re still looking to see how predictions in everything from cars to investments play out — but also seeing similarities some parallels with what America experienced a century ago. That starts, of course, with a coronavirus pandemic that had striking similarities to the Spanish Flu pandemic that began in 1918 and continued into the early 1920s. Read on for more about that, and to see how history does and doesn’t repeat itself in other ways, and share your reactions and observations in the comments.

Related: 12 Things We Can Learn From the Great Depression

1920s: The Spanish Flu

In the fall of 1918, a mutated version of the virus that claimed its first victims in the spring made its way around the world, causing the death rate to escalate quickly, eventually killing as many as 50 million people worldwide, 675,000 of those being U.S. citizens.

During this time, the CDC says, “no coordinated pandemic plans existed in 1918. Some cities managed to implement community mitigation measures, such as closing schools, banning public gatherings, and issuing isolation or quarantine orders, but the federal government had no centralized role in helping to plan or initiate these interventions during the 1918 pandemic.” The Spanish flu didn’t truly end until sometime in the early part of 1920, and its repercussions were felt well beyond.

2020: Coronavirus

Fast-forward 100 years to news that was eerily similar. The first coronavirus cases were reported in China just before the dawn of a new decade, and the pandemic continues, having killed an estimated 6.5 million, with about 1.1 million of those in the United States. Healthcare has made significant strides in the century since the Spanish Flu, and the general population is better informed — and therefore able to implement life-saving measures — than those who lived 100 years ago.

1920s: Culture Wars

As European economies recovered and the USA boomed in the wake of World War I, the number of Americans living in cities exceeded the number on farms for the first time. Many began to hold increasingly liberal views on drug use and sexuality, not to mention the equality of women and minorities.

These cultural shifts provoked considerable backlash. “There are so many current trends that started in the 1920s,” says Chip Rhodes, historian and author of “Structures of the Jazz Age.” “Pop cultural trends away from tradition toward a focus on entertainment and pleasure, [and] trends away from religion and ruralism toward studio-monopolized movies.”

2020s: Culture Wars

Americans are still ideologically polarized, but the intervening century has made it harder to define the battlefronts of a culture war along strictly geographic lines. “There’s not so much a divide between urban and rural as a generational divide,” says Jay David Bolter, a new media expert and professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

He says digital media use among younger generations has entrenched this separation — the old filtering their perspective through television and film, the young through social media and video games. The urban and rural divide still exists on our political landscape, but expect that to get less clear-cut.

1920s: Finance

America’s wealth more than doubled in the years between 1920 and ’29. Most of this wealth funneled into finance and industry, but enough trickled down to low-level employees to let them participate in a new consumer culture.

According to Rhodes and other historians, the crash of ’29 resulted from overproduction, “an inherent contradiction in consumer-oriented capitalism,” with banks loaning more than they could cover and companies producing more than the middle or working classes could afford. The same excesses that powered the ’20s became its downfall.

Trending on Cheapism

2020s: Finance

If the 2010s are akin to the 1920s – the decade of seeming financial prosperity belied by growing inequality – it might be reasonable to predict the 2020s mirroring the 1930s, when overspeculation came crashing down and economic woes came to the forefront.

With corporate profits plateauing, financial prognosticators in 2019 were already trying to pinpoint the start of the next crash. Now, they have a war in Ukraine, persistent supply-chain issues, stubborn inflation, and a labor shortage to contend with.

Related: What You Need to Know About Buying a House Now

1920s: Alcohol Prohibition & Organized Crime

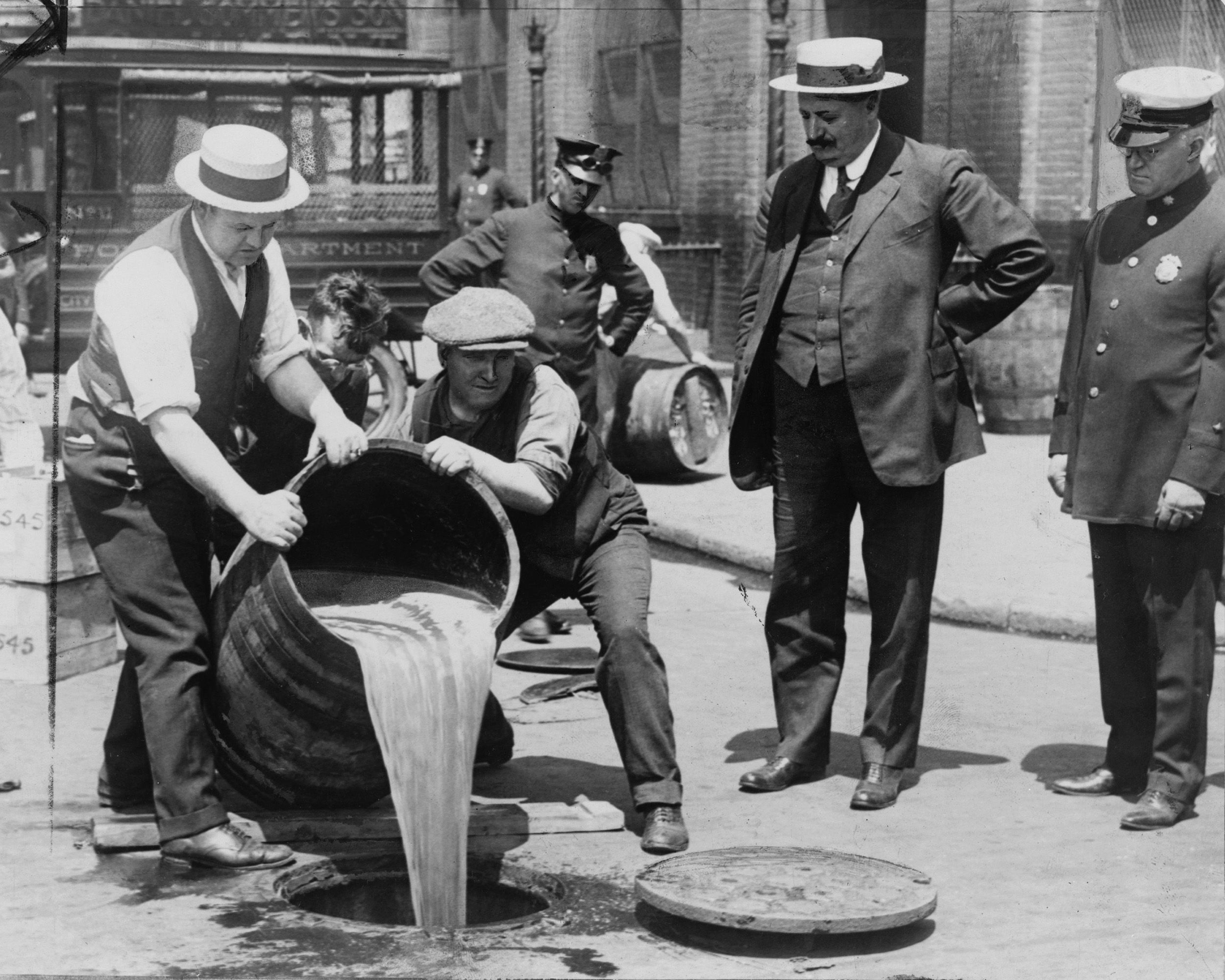

America’s Temperance Movement achieved its primary goal Jan. 16, 1920, when the 18th Amendment’s ban on making and selling intoxicating liquors took effect. Instead of going away, alcohol just went underground, with speakeasies replacing taverns and more potent moonshine supplanting milder forms such as beer. The continued demand meant the task of transporting and selling booze fell to criminal organizations that had been just petty street gangs before.

Bootleggers and mob bosses such as Chicago’s Al Capone amassed enough power to influence cops, lawyers, and politicians in their favor, and they consolidated into syndicates to control more turf. By the time Prohibition was repealed with the 21st Amendment in 1933, it was too late to pull the plug. Organized crime pivoted to income streams such as drugs, gambling, and prostitution.

Related: From Bootleggers to Checkered Flags: The History of NASCAR

2020s: The War on Drugs & Organized Crime

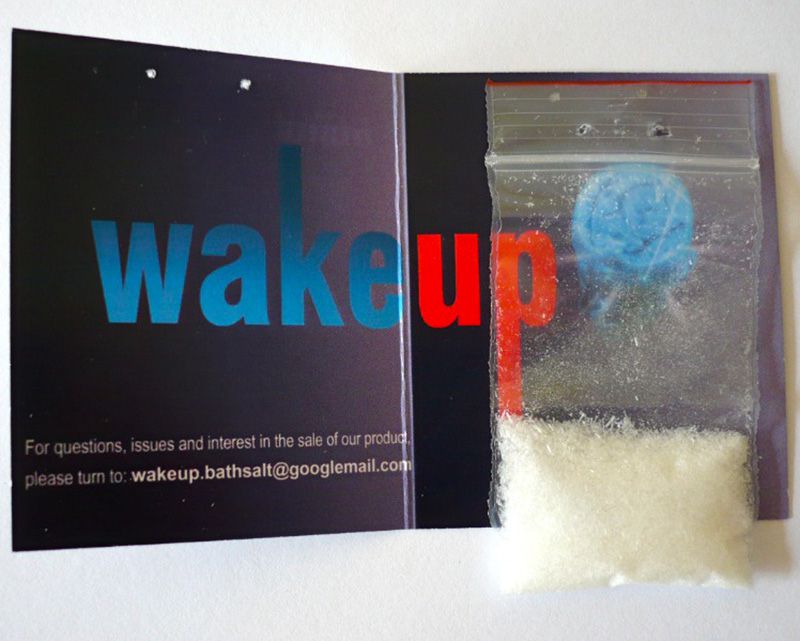

Today, the legal market for alcohol is steady if not trending downward, given the renewed competition from recreational cannabis and the rise of alternative beverage forms such as hard seltzers. A more apt point of modern comparison to Prohibition might be the ongoing war on drugs.

There are now whole economies powered by the illicit drug trade, particularly concentrated in Southeast Asia’s Golden Triangle. Such organizations’ global spread and sophisticated use of digital technologies and international shipping services mean they’ll only become more elusive to law enforcement agencies.

Sign up for our newsletter

1920s: Cannabis

Marijuana really caught on in the 1920s, particularly among jazz musicians and others in show business. It gained prominence, no doubt in part due to Prohibition’s crackdown on alcohol, so while liquor bootleggers and speakeasies were under close legal scrutiny, cannabis clubs in major cities, or “tea pads,” were largely tolerated by authorities.

It wasn’t until 1930 that the U.S. Federal Bureau of Narcotics made the substance a primary target of its propaganda campaign, depicting users, particularly foreigners and minorities, as dangerous, violent addicts.

2020s: Cannabis

The 2010s saw a major turnaround in U.S. policy regarding cannabis and non-psychoactive hemp, and the industries’ continued development is looking like one of the biggest economic stories of the 2020s.

While researchers have made up for nearly a century of lost time studying the crop and optimizing its applications for fiber, food, and medicine, people’s polarized perceptions of the Schedule 1 substance appear to be changing.

Related: Surprising Facts About the Marijuana Industry

1920s: Income Gaps

While swanky speakeasies and flapper fashion styles were a part of the so-called Roaring Twenties, they existed in a context of widespread social and economic inequality that’s easy to forget. Urbanization and new forms of mass media highlighted these wealth gaps, reminding struggling immigrants and rural workers of the luxuries they lacked. “The most misrepresented developments [of the 1920s] are often about ‘prosperity,’” Rhodes says, “which tend to focus attention on the wealthy and to ignore rampant poverty — a wealth gap much like the one that exists today.”

2020s: Income Gaps

The ultra-rich haven’t possessed as great a share of America’s wealth as they do today since the Jazz Age. Yet again, new media forms — in this case, the internet — have brought renewed attention to inequities in income and treatment by employers and law enforcement agencies. Without the same increasing prosperity as the 1920s, however, social mobility remains stalled, with a lessening supply of stable jobs for even the well-educated. “If we don’t figure out something about wealth disparities, there are many things that could go wrong,” Rhodes says.

1920s: Technological Change

If World War I marked the debut of industrialization on the battlefield, the Jazz Age saw it enter the lives of ordinary citizens. Fridges, vacuums, telephones, radios, and electricity all became household fixtures. These technological innovations connected people and populations across great distances, contributing to the cultural progress and tensions that played out throughout the decade.

Related: Products You Never Thought Would Be Obsolete

2020s: Technological Change

Culture is again being transformed by what might be called “digitization,” merging computer processes with physical ones. A few specific predictions on what that might look like from Future Timeline include internet use expanding to 5 billion worldwide, the proliferation of 5G connectivity, 3D printing becoming more common (particularly for medical purposes), and continued blurring of the lines between human and artificial intelligences.

While technology promises to make some industrialists very rich, the ultimate impact on our overall physical, mental, and even economic health is still hotly debated.

Related: Things We Use All the Time That Didn’t Exist 10 Years Ago

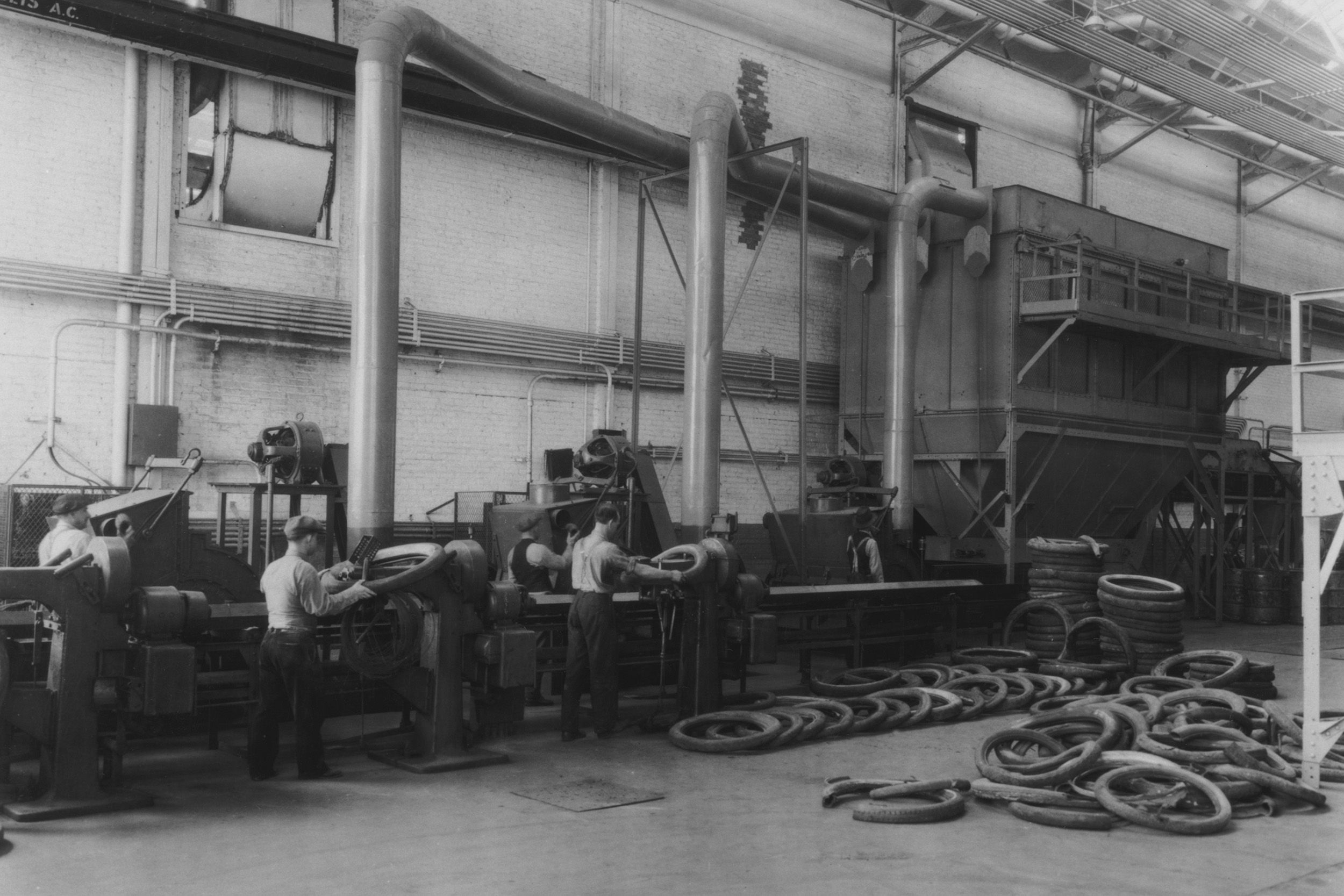

1920s: The Automation of Work

Despite the booming economy, many in the 1920s were concerned that new technologies and mass production methods would render human workers obsolete. The new focus on streamlining and efficiency meant workers did more monotonous single tasks to speed up production.

“While making work more routinized, more alienating, mass production also led to increased wages,” Rhodes says. “Henry Ford realized that he had to pay workers a wage that would enable them to be both workers and consumers. Long-term, it has gradually led to the disappearance of stable jobs that paid livable wages for workers.”

2020s: The Automation of Work

People around the world again live in fear of being replaced by technology, specifically in the workplace. Automation and artificial intelligence are already rendering many tasks that once relied on middle-skill occupational workers redundant. It’s not all fire and brimstone, however.

Bobby Warren of Budgeting Couple predicts that AI will become more routine as a way to streamline financial decisions, and with “secured, read-only access to our bank and credit card accounts, they can scan our transactions, see what we are paying, and compare it with a database of users to see if we are overpaying. Take a look at what AI-based robo-advisers are doing in the investment world, with trillions of assets under their management.

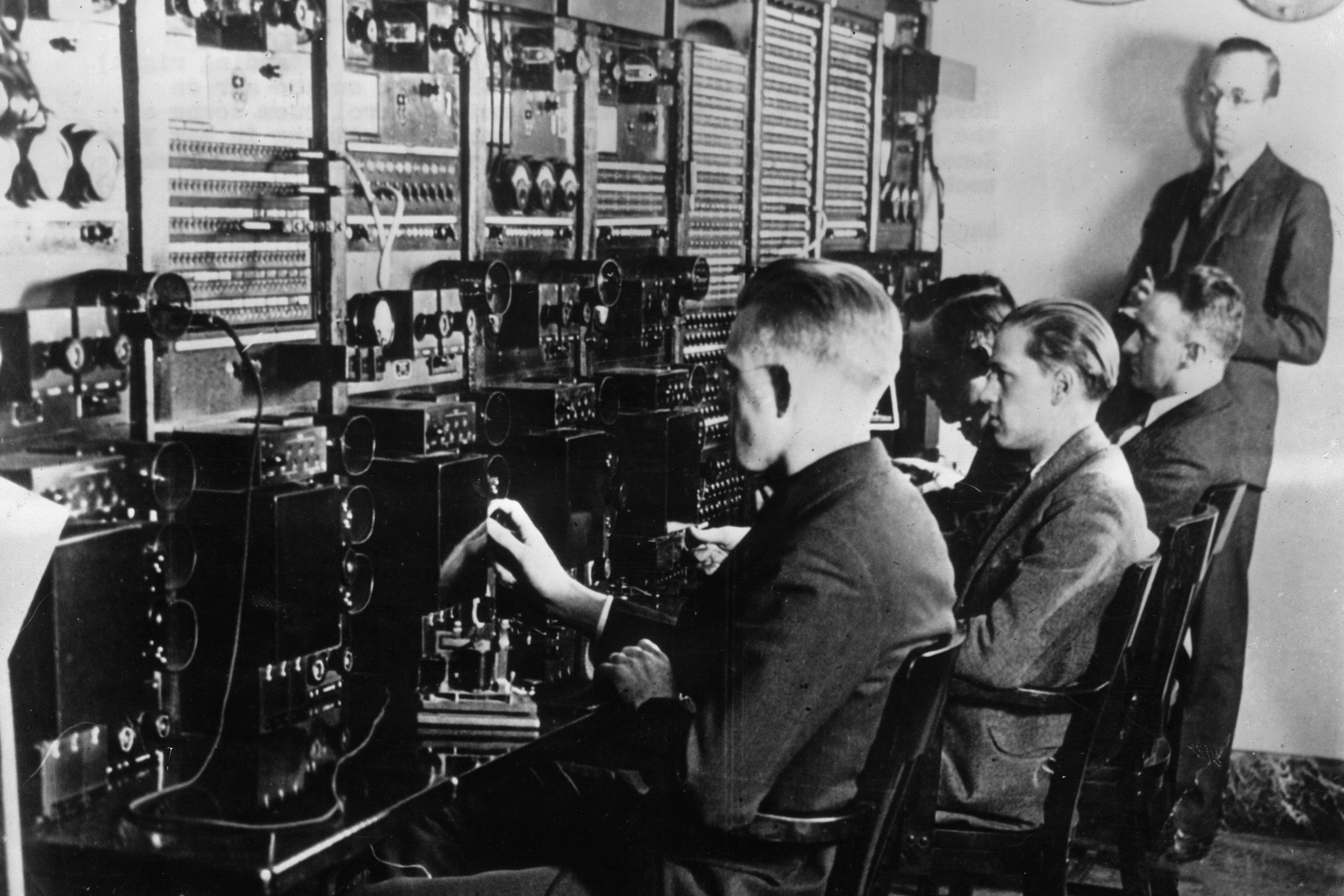

1920s: Consumer Culture

New modes of transportation and communication in the 1920s connected huge swaths of the population that had previously been isolated culturally and economically from one another. After the first commercial radio station launched in Pittsburgh in 1920, more than 12 million households had radios by the end of the decade.

Suddenly, people all across the nation could buy the same goods from the same makers and aspire to the same statuses, spawning a homogenized, geography-spanning “mass culture.” “Mass consumption [endangered] local cultures,” Rhodes says. “The influence of the movies, radio, and magazines created a desire for mass production commodities that were copies of what local residents had seen.”

2020s: Consumer Culture

Looking ahead in the 21st century, mass consumption still reigns, but with some caveats — namely owing to the ongoing upheaval of digital outsourcing and Web-based business models. Social media and online advertising personalize what each consumer sees, while companies deploy increasingly sophisticated algorithms to monitor and predict our behavior, profiting from a one-sided exchange of data — the new currency.

However, even as companies profit from our digitization, we can use it to connect. As Bolter says, “You don’t have to live in the same place anymore to be a community.”

1920s: Transportation

Though invented in Europe in the late 19th century, the automobile really took off in 1920s America. By 1928, 20% of Americans owned a car, thanks in large part to the system of assembly line-style mass production introduced by Henry Ford to make his signature Model-T more affordable.

This method of production, combined with the automobile itself, transformed the U.S. economy, bolstering existing industries and creating new ones. At the same time, transnational air travel was being proven viable by pioneers such as Charles Lindbergh, who completed the first solo flight across the Atlantic in 1927.

Related: The Greatest American Inventions of the Past 50 Years

2020s: Transportation

More and more private companies (including Amazon’s Blue Origin and Tesla’s SpaceX) are wading into space travel, even designing consumer-oriented experiences such as those on offer from Virgin Galactic. Meanwhile, car travel may be on the verge of transforming.

Driverless trucks, taxis, and buses may yet be in use by the end of the next decade. A switch to electricity and other renewable energy sources is well underway, and more commuters may come to rely on ridesharing or other services that lower private car ownership. Finally, high-speed train travel could see some major innovations, such as through magnetic levitation, or “maglev,” trains being developed in China and South Korea.

Related: Electric Cars That Are Cheaper Than a Tesla

1920s: The Rise of Film

“The auto industry, personified by Henry Ford and mass production, and the film industry, personified by the stars, not the producers, used the same production process — and for the same reasons,” Rhodes says. Cars, clothes, and movie attendance were all based on an appeal to luxury and leisure.

Often showcasing an opulence the average citizen could now supposedly aspire to, silent movies spawned film’s first enduring, nationally known celebrities before being displaced by sound films beginning in 1927. By the end of the decade, 95 million cinema tickets had been sold, with an estimated three-quarters of America’s population visiting every week.

Related: Historic Movie Theaters Across America

2020s: The Demise of Film

The film medium — or at least Hollywood — is in an existential spiral. The only truly stable major studio remaining is Disney, a once-scrappy animation startup that is now gobbling up big-name competition, such as 20th Century Fox, to build its audience using endless cross-format ties and series repackaging.

“Movies still have an extremely large community, but there are lots and lots of people who don’t belong to that community and don’t follow what’s happening in Hollywood the way they did, even into the ’80s and ’90s,” Bolter says. Film won’t go away in the 2020s, but it will continue to transform, likely into something less centralized and more challenging to categorize.

1920s: Feminism

The 19th Amendment, granting women suffrage, took effect in August 1920, and the ensuing decade saw women asserting their independence culturally and economically. Millions began working in white-collar jobs and participating in a new consumer economy, while the emergence of birth control devices lessened the necessity of motherhood.

“In general, the only tangible progress that followed in the wake of suffrage was the cultural progressivism of the flapper, in which women insisted on power in their personal lives but lost interest in political progressivism,” Rhodes says. “The long, ongoing fight for equal rights began in the 1920s, driven by pioneers in women’s rights, but in a largely self-contained community.”

2020s: Feminism

Today, the fight for gender equality is concentrated more on achieving economic justice in the workplace and abolishing coercive sexual mores, and it’s hard to guess where it will go from here, aside from incrementally forward. It’s likely that gender definitions will only become more fluid and transgender or nonbinary identifiers more common, though not without conservative cultural backlash. The arrival of male contraceptives in the coming decade is also likely to have an impact.

Related: Careers Where Women Are Paid More Than Men

1920s: Race

“On the positive side, urbanization was (and still is) the engine for diversity and racial mixing that has brought whites and blacks into greater contact in new settings,” Rhodes says. “This has led to healthy, cultural sharing, but it has also led to increased segregation within cities.” After World War 1, more than 1 million African Americans relocated from the segregated South to northern cities in what’s now known as the Great Migration.

The Harlem Renaissance, which included literature by Zora Neale Hurston, poetry by Langston Hughes, and the jazz of Louis Armstrong and others, blossomed in New York, but racial prejudice was still widespread in Northern cities. After the NAACP and others were able to negotiate anti-lynching onto Republican Warren G. Harding’s presidential platform in 1920, membership in the Ku Klux Klan reached an all-time peak of 4 million to 5 million members in the first half of the decade, including in northern states such as Indiana and Illinois.

2020s: Race

Polarization over racial issues hasn’t gone away, and when asked to predict the future, Rhodes says, “the war over race and immigration will only become more violent.” As in the urbanized ’20s, some segments of the culture embrace racial integration and justice while others reject it — only now these groups are separated by digital algorithms and media silos as much as by urban redlining.

“The economic, political, and cultural ‘wars’ that split the U.S. in the ’20s are eerily similar to the conflicts of today,” Rhodes says. “Arguably, through the intervening decades, we made genuine (if slow) progress on these most vexing issues. But it does seem like that progress was always fragile and sometimes just rhetorical; so we’re back to the 1930s, I fear.”

1920s: Music

“Jazz was both the image and engine for the new, cosmopolitan, racially mixed culture,” Rhodes says, “and also sought to tap into an emotional or spiritual impulse that ‘civilized’ America had repressed.” The improvisational genre became a major sensation at dance halls while more and more records sold (100 million in 1927 alone), offering black people a rare means to profit from the era’s economic prosperity.

The reaction against this supposedly “depraved” genre seemed no match for the spread of mass culture’s first runaway pop music sensation.

2020s: Music

As a liberating, youth-oriented musical force, jazz was eventually supplanted by rock. It’s unlikely we’ll see another form of pop music capture the zeitgeist so completely in our networked future, except perhaps a hybrid of genres we already know.

“There’s no real cultural center,” Bolter says. “Even the big pop music superstars aren’t really known by everyone. There’s not the same claim to cultural dominance that there was even in the era of rock music in the 1960s.”

1920s: Fashion

Thanks to advertising, mass production, and disposable incomes, clothing became a major object of desire, while also modernizing in a few crucial ways. The ’20s — particularly the late ’20s — were the age of the flapper, a label for women who sported the new, corset-free styles.

The idea of the liberated “new woman” was a reflection of their renewed economic power during the war and political power after the passage of the 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote. As for men, formal attire became less of a necessity, and sportswear became popular.

2020s: Fashion

Some trendsters predicted a resurgence of Roaring ’20s styles such as silk stockings and bob haircuts for the 2020s. It could still happen. But singular fashion trends, and specifically American ones, are less likely to exert the same gravitational pull they did at the dawning of mass media.

Vogue forecasts that China’s geopolitical prominence will soon translate into the fashion world; that production of pants and other garments will have to switch to sustainable sources such as algae; and that what we wear may soon gain 5G connectivity.

1920s: Celebrity

“The cult of celebrity and the allure of fame took firm hold in the 1920s,” says Rhodes, whether people were idolizing film stars such as Charlie Chaplin and original “It” girl Clara Bow, athletes such as Babe Ruth and Jack Dempsey, or socialites such as Zelda Fitzgerald and Coco Chanel.

Thanks to mass consumption and our long-standing tradition of “working your way to the top,” America in particular became a “mimetic culture” in which consumers imitate those they aspire to be, even if the ideal of fame was only rarely tied to the old-fashioned values of hard work and humility.

2020s: Celebrity

The concept of movie stars and public celebrities known and beloved by all is becoming less and less applicable. Different cultural communities have their own celebrities, which can include stars of their own YouTube channel, and fans now expect them to be more accessible and real rather than untouchably luxurious.

“There’s this incredible diversity of participation that we’re seeing now in our culture, that I think is quantitatively different from the way culture was organized even 100 years ago,” Bolter says. “It started in the 2000s with user-generated content, and now this is a phenomenon where we have individuals and groups of people generating their own content that has large audiences, if not on the same scale.”

Related: Celebs Whose First Job Was Worse Than Yours

1920s: Energy

During the 1920s, while fragmented electricity grids were just maturing in towns and cities (the national grid not coming on until 1933), petroleum and, to a lesser extent, natural gas were fast gaining on coal among the nation’s energy sources.

Foreign companies began drilling operations in South America, with Venezuela becoming the world’s second-largest oil-producing nation. Petroleum would overtake coal in the midcentury and has remained our primary means of energy ever since.

Related: Which States Have the Highest Gas Bills?

2020s: Energy

“Politically, if we don’t recognize the lessons of science about climate change, well, that will be that,” says Rhodes, referring to the rising sea levels, natural disasters, and mass migrations and extinctions that science forecasts if the human-made buildup of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere continues at the current pace.

Renewables (including solar, wind, nuclear, and biofuel), changes in agricultural practices, and engineering projects that recapture carbon from the air back into the Earth could be America’s new direction.

“For the first time since the 1950s, the U.S. produced more energy than consumed at more than 100 quadrillion BTUs,” notes Spencer McGowan, a certified investment management analyst. “Renewables and, of course, carbon-reducing natural gas will play a key part in U.S. energy dominance.”